I came to read The Four Loves by a strange coincidence.

A friend in Albuquerque had reintroduced me to the author’s works only weeks before. If it hadn’t been for this, I would have taken no notice of the little volume as I wandered the library of an American university’s Gaming, Austria, campus. Gaming’s main claim to fame is the centuries-old Carthusian monastery from which Albrecht II von Habsburg ruled his domain, so it already struck most of the villagers as odd that an American journalist should visit at all. But it was to me especially weird that I should find an English library, and that in this English library I should find a bookshelf labeled “Book Exchange, take these books!”, and that on that shelf I should find a book I’d considered reading before I left Albuquerque for Austria.

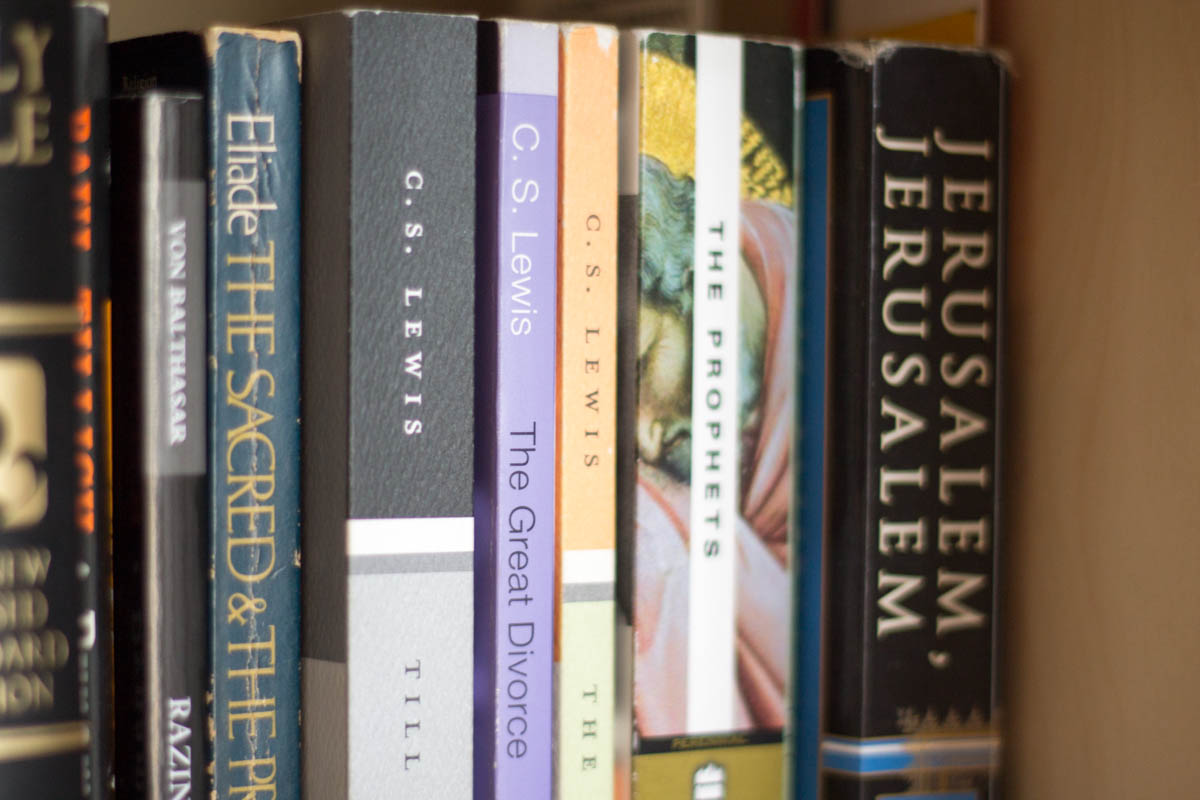

I picked it up, and over the course of a week in Gaming I read it. And thus it became one of the three books that led me to change my mind about C. S. Lewis. The Four Loves, The Great Divorce, and Till We Have Faces—taken together, these three books converted me from Lewis-hater to surprised fan. What do they have in common? Each one shows us that even love, even honest love, can spoil. And this is a moral problem of the first order.

After a surly encounter with Mere Christianity in high school, I largely wrote Lewis off as an intellectual lightweight and religious crank. He seemed to peddle the kind of apologetics that does more to expose the cracks in Christianity than it does to fill them with solid mortar. To a newly self-conscious atheist coming into his own, that seemed not quite respectable. But I’ve come to see Mere Christianity as an outlier. In spite of all its arguments, it just doesn’t have the kick of the other entries in Lewis’s library of moral reckoning.

For Lewis’ great strength lies not in persuading his readers about the truth of Christianity—of that he’d probably be first to admit—but in shaking us with the lucidity of his moral insights. We have in Lewis a kind of latter-day Christian Aristotle: a plainspoken but penetrating analyst of human vice and virtue. Lewis can move even a committed atheist to moral dread, but not by invoking fire and brimstone. All he has to do is look at himself and tell us what he finds. And for the most part, the only possible response is, “Goodness! What if I do that, too?”

And so begins one’s first session of moral therapy a la Lewis.

Lewis is a disturbing writer. It’s not that he sets out to shock. He doesn’t have to. His subject is shocking enough on its own because his subject is people. Far more than panegyrics on the wisdom of Christianity (although there’s plenty of that to be sure), Lewis’ books are sober diagnoses of all the ways we fail to do the things we think we should. But they’re not the diagnoses of the moralist. Lewis is not the Physician, and he’s too wise to put himself above the sinful masses.

Through a combination of shrewd observation and ruthless introspection, he gets to the heart of the most mundane, the most common—and therefore the most unsettling—vices. Consider an example from the second chapter of The Four Loves. The implied framework of The Four Loves comes directly from the four Greek words for love, storge, philia, eros, and agape. In Lewis’ schema, Affection, Friendship, Eros and Charity.

The second chapter concerns storge, Affection. Lewis observes that many of us feel entitled to the Affection of others. We claim it by right. Those who deny us are “cold” or “broken.” It’s “unnatural” for children not to love their parents, for coworkers or classmates not to fall into little knots of mutual regard. But who’s really the vicious one here?

If all goes well, Affection will arise and grow strong without demanding any very shining qualities in its objects. . . . [But] What we have is not a “right to expect” but a “reasonable expectation” of being loved by our intimates if we, and they, are more or less ordinary people. But we may not be. We may be intolerable. [1]

“We may be intolerable.” I feel a kind of odd relief at coming to this brutal possibility. Perhaps this was a more acceptable sentiment in the post-war England of Lewis’ acquaintance than it is in the present American climate, conditioned by the cults of perfection and self-esteem. But I appreciate Lewis’ forthrightness. Not simply because it flouts the American preoccupation with positive self-image, but because well, we might be. And this is a relief. For I can change myself. Others I cannot change.

Of course, the true targets of this passage are those who cannot even conceive that they might be intolerable. But even these people, Lewis does not berate, for every possibility he sees also in himself. He’s dispensing not judgement but moral therapy. Before you can fix the problem, you have to know that you have one. Though we may think our problem is that others don’t love us according to our dues, we probably have another thing coming. They may love us exactly as much as we deserve. We should remember to look at ourselves first when we ask where love went wrong.

The lessons of Lewis remain unreckoned with in my own most comfortable circles. Secular types more or less never move past the intellectual prudery and highmindedness that dismisses works of faith as so much claptrap. None would be so stupid as to deny the stylistic appeal of Lewis’s writings, but many are stubborn enough to deny them any secular relevance. That’s a shame.

As condemnations of life lived without utter concern for the good of others, these books accuse everyone—not in the manner of the prophets of Israel, uncompromising in their conviction of Israel’s disobedience, but in that of a equal, but wise friend. Even the most overtly Christian of the three books, and even the most overtly Christian of its passages, can’t really be ignored by the thoughtful atheist. Not because they compel her to consider the supernatural—they don’t—but precisely because, for all their supernatural content, the heart of the matter is really moral. This is true even when Lewis is engaged in supernatural allegory.

In The Great Divorce, Lewis takes a bus journey from Hell, a shadowy town of eternal twilight, to Heaven, a light-filled valley where even the grass is more solid than the ghostly forms of Lewis and his companions from Hell. In the exact middle of the book he meets the heavenly incarnation of his Scottish teacher, George MacDonald, who explains the peculiar nature of salvation, of good and evil.

Both good and evil, when they are full grown, become retrospective. Not only this valley but all their earthly past will have been Heaven to those who are saved. Not only the twilight in that town, but all their life on Earth too, will then be seen by the damned to have been Hell. . . . And that is why, at the end of all things, when the sun rises here and the twilight turns to blackness down there, the Blessed will say “We have never lived anywhere except in Heaven,” and the Lost, “We were always in Hell.” And both will speak truly. [2]

One need not believe in survival after death to grasp the point of this passage. In naturalized terms it might run thus: We live in a moral heaven or hell of our own making. Everything in us, the good with the evil, forms a part of our moral shelter. What matters in the end is what kind of structure we built, and not so much the tally of promises broken and kept. If we build ourselves a prison, the good bricks pen us in as well as the bad. Even love goes bad then.

As a moral heuristic, this is excellent. It reminds me a bit of Friedrich Nietzsche’s so-called doctrine of the eternal return. Nietzsche posits an enormous temporal cycle, cosmic in scope, in which every event and every life repeat endlessly for eternity. Faced with the prospect of making the same choices over and over again forever, I come to see my life as a unity, composed not so much of segregable events and choices but a totality that stands or falls as a whole, that entity called Me. In the same way, Lewis’s tale compels us to take in our lives at a single glance. He makes us look at the house we’ve built.

Jean-Paul Sartre is famous for the quip, “Hell is other people.” Clive Staples Lewis ought be famous for replying: “No, Jean-Paul, Hell is ourselves.”

Lewis’s moral vision extends beyond the confines of his explicitly theological works, roosting quite as comfortably in the fiction of Till We Have Faces as in the philosophy of The Four Loves. And just like The Four Loves, Till We Have Faces draws directly from Classical sources, this time from the story of Cupid and Psyche. Lewis’s tormented heroine is not the kidnapped Psyche, but Orual, her perspicacious but less-favored sister and future queen of the realm.

Lewis cleaves faithfully to the classic formula of the myth, but he does not hesitate to embellish according to his usual flair. It should come as no surprise that his improvisations tend to bring into sharp relief the moral landscape of the myth. One detail breaks out like heat lightning at the book’s first climax. As in the myth, Psyche’s parents offer her as a sacrifice, and the son of Aphrodite spirits her away. Orual, known to her sister as Maia, pursues Psyche into the mountains. At her second visit, determined that Psyche should gaze on her husband despite his orders, Orual contrives a sure means to bend Psyche to her will.

“An end of this must be made,” I said. “You shall do it. Psyche, I command you.”

“Dear Maia, my duty is no longer to you.”

“Then my life shall end with it,” said I. I flung back my cloak further, thrust out my bare left arm, and struck the dagger into it until the point pricked out the other side. [3]

What choice does Psyche have? What can anyone do when their loved ones weaponize love?

For the weapons of love are more than Cupid’s arrows—and usually less benign. Lewis’s books read like a catalog of such weapons and the people who wield them. The possessiveness of the mother whose son is “mine, mine, mine, for ever and ever.” [4] The jealousy of those who, far from glorying in the mirth of their loved ones, cannot stand to be rejoiced without. The snobbery of friends, whose love for their exclusive circle eclipses their regard for the world beyond. The anger of lovers who, having made of the beloved the entire world, heap every pain at her feet and say, “These are the works of love.”

These weapons called love—at least by those who brandish them—have one thing in common. They reckon the wages of love more valuable than the labor. The snobs want to bask in their likemindedness, secure that they’ve vetted all comers with their litmus tests. They want a simple enumeration of someone’s beliefs, accomplishments, and birth to stand in for the labor of loving all comers, of loving all those whom it is given to you to love. The jealous care not for loving, only for being loved. They would have the payment, but not the work. The over-possessive parents would shape their children into mirrors, reflecting their own love forever in perfect appreciation of their pain and want and helpless adoration.

And the lover. The lover is perhaps most guilty of this common sin. So long as loving pays nice returns, he’ll praise it to the skies. When the crash comes—then he never made a worse decision than loving her.

Here’s something that I learned from messing it up repeatedly and have the pleasure of learning again from Lewis. Love’s labor’s the thing. It is not for the wages of love, for the pleasure to come, that we ought to love. We ought to love for the present joy of laboring in love, not to store up our wages for the future. If we put our trust in love’s wages and take no note of the joy of love’s work—then we’re liable to lose altogether our trust in love. Should that time come when the bonds and bullion and IOUs stacked up in our heart’s safety deposit box all vanish in a cloud of hurt feelings, what’s to stop us forsaking fickle love?

For that danger plagues even those who might rejoice in love’s work. Then we might say with the disillusioned: If you would not be disappointed, don’t invest in things that pass away. For the Buddhists, this is a means of effacing the self and achieving nirvana. Some Christian thinkers exhort us to give our hearts only to God, for only that which does not fade will never hurt you.

No other piece of common advice has ever struck me as so inhuman.

Why should we so fear disappointment? We cannot store up anything for eternity. What then is so frightful about losing what we love that it merits loving nothing and no one instead? For all our metaphysical differences, Lewis and I reach identical conclusions about the risk—and it is a risk—of loving. And this despite his own prudential nature.

Of all arguments against love none makes so strong an appeal to my nature as “Careful! This might lead you to suffering.” . . . When I respond to that appeal I seem to myself to be a thousand miles away from Christ. If I am sure of anything I am sure that His teaching was never meant to confirm my congenital preferences for safe investments and limited liabilities. I doubt whether there is anything in me that pleases Him less. [5]

I came around to liking C. S. Lewis. Not because we agree about everything. Not because he’s an authoritative interpreter of a religious tradition to which I subscribe. But because he has moral vision. It’s like a superpower with this guy. Not unlike the depth psychologists against whom he periodically railed, Lewis could dive into the human personality and come back with its most glittering treasures and its most odious refuse. But better than this, he exposed all of the little ways we find of breaking promises, harming others, and patting ourselves on the back later. He does not let us escape because he does not let himself escape.

Wading this deep into the everyday, ordinary vices of mankind, you couldn’t blame him if sometimes he let the anger overcome his patience. But he never does. Instead we walk together through the gallery of our misdeeds. And sometimes he stops and says, “Now see that? We could’ve done better there.”

[1] Lewis, C. S. The Four Loves. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012. 40. Back.

[2] —. The Great Divorce. New York: HarperCollins, 2001. 69. Back.

[3] —. Till We Have Faces. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012. 164. Back.

[4] The Great Divorce. 103. Back.

[5] The Four Loves. 120. Back.