By and large, A Series of Unfortunate Events[1] concerns itself with the upper middle class. Think of the first four books’ most sympathetic characters: the Baudelaires, Justice Strauss, Uncle Monty. All of these people live in spacious houses with well-tended gardens.

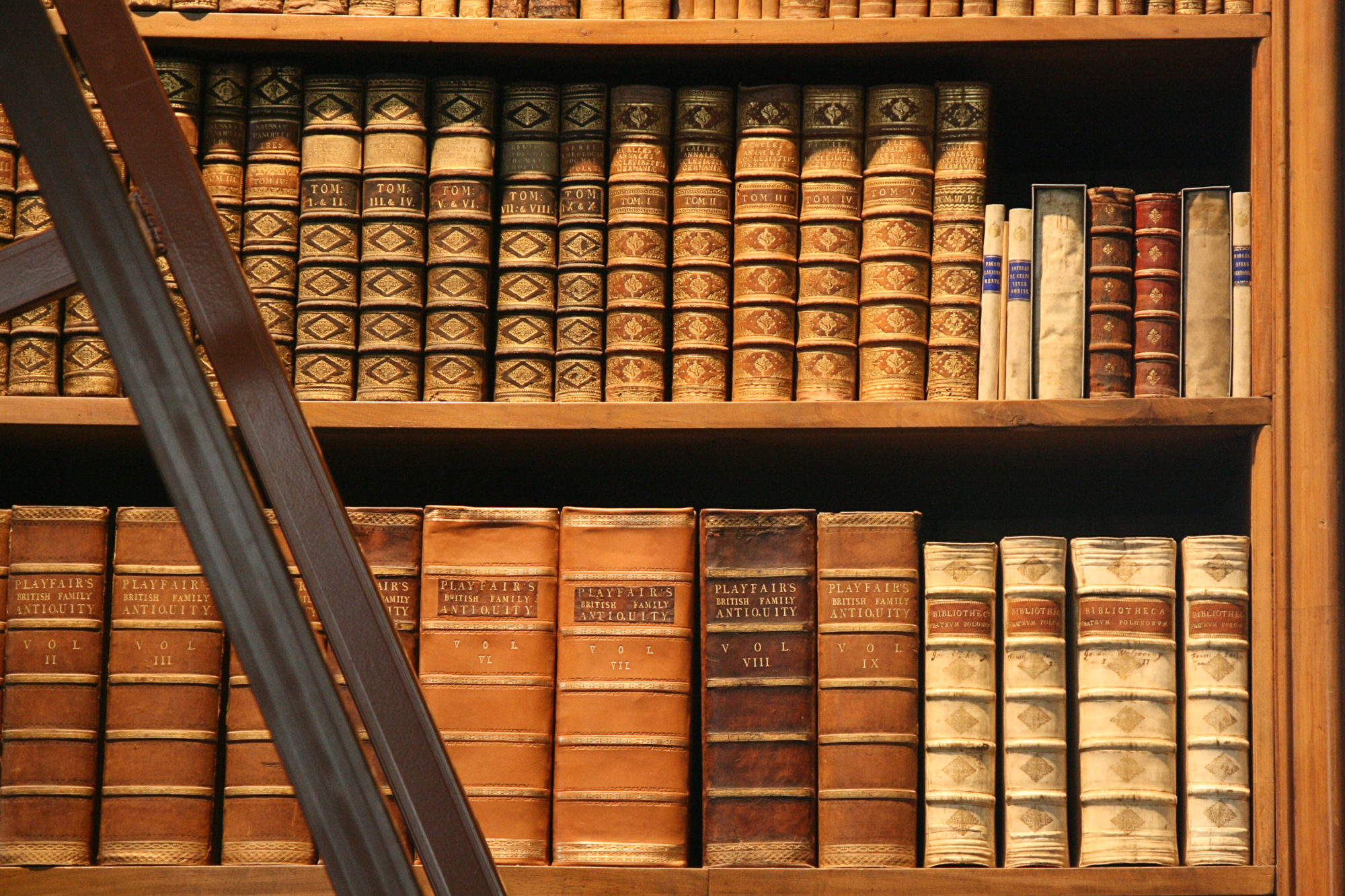

These most esteemed characters aren’t just wealthy; they also parrot a set of fairly snobbish values. Libraries are repeatedly offered as the only havens in an unsafe world—and not public libraries, ornate private libraries. “The world is quiet here” is the catchphrase[2] of the noble secret organization. What kind of quiet is this? The quiet of solitude in your private library? The sort of quiet that developers hope to provide in their gated subdivision? The kind that drives them to lay out roads like mazes to keep out traffic?

All of this begs the question: where is the working class in this story? In short, almost nowhere. Everyone has a sizable house, a prestigious job, a business of their own, or (in the case of the villain) a mysterious title. Count Olaf’s five henchmen comically cram into an old sedan with him whenever they have evil to do, but in most other respects they belong more to neverland than to any recognizable real-world social class, so I’ll leave them out of this accounting.

And so the burden of representing the working class falls almost entirely on the workers at The Miserable Mill‘s titular lumber company. They perform dangerous labor for nothing but chewing gum and coupons. And their reason for accepting this unbearable lifestyle? Literal hypnosis at the hands of the company optometrist.

No sympathy for the capitalists here. Come to think of it, none for their exploited workers either. Somehow I doubt that a mill worker would appreciate being represented by a group of people defined by their tendency to recite in unison their loyalty to their employer. Talk about a lack of agency.

The workers do eventually revolt, but when they do it’s because—spoiler—the upper middle class protagonists learn the secret to free them from their hypnosis. Someone more charitable and well-versed in socialism than me might draw comparisons to Leninism here. I’ll just go with my gut and call it a Messiah complex.

Am I reading too much into the imaginative details of a children’s story? Contrast this with a few other particularly vivid satirical elements of the series: a banker who chooses to live in a tiny house sandwiched between skyscrapers rather than move outside the business district; a researcher who is more afraid of his academic rivals than a murderer at his doorstep. All these farcical elements come from pointed criticisms of the groups that these characters represent. They make the condescension in The Miserable Mill seem all the lazier (or all the more malicious). In so many other respects, Daniel Handler’s[3] funhouse-mirror vision rings damningly true. It’s a shame he can’t do better with respect to class.

[1] The TV series, not the books. Though based on my memory of the books, I think most of the points here would remain salient.

[2] Since the TV series only shows someone saying this once, I am relying on the books in calling this a catchphrase. Considering that this becomes a fairly major point in the books and the show has largely been faithful to the books, I don’t think this is unfair.

[3] Also, I should credit/criticize the folks at Netflix that adapted his work.